Picture this scenario. You have just been told that your child has a fracture of the distal radius and ulna. The doctor showed you the X-rays and you can clearly see that the bones are broken and bent out of shape.

The first question many parents ask in this situation, “Is my child going to have to undergo surgery?”

As a surgeon, one of the most important decisions that I make is not how to do a surgery, but whether surgery should be done at all. Surgery – especially in kids – should be approached cautiously and done only when there are clear benefits.

Fractures of the wrist are one of the most common injuries in kids. The wrist has many bones, but the radius and the ulna are two that are typically injured the most. In kids, 20 percent of all broken bones occur in these two bones.

Luckily, almost all of these fractures can be treated with casts that are applied and removed right in the office. Gone are the days of heavy plaster of Paris casts. Casts today are made out of fiberglass, which is lighter and more durable. They also come in a whole rainbow of colors from which the kids may choose. They are typically on for three- to six-weeks.

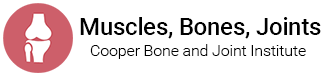

One of the great things about youth is that even those fractures where the bone is clearly out of shape can often be treated in a cast. Kids not only heal but remodel. Remodeling is a process where broken bones reshape themselves over time back into their normal appearance. These results can be quite dramatic! Take for example the case of a five-year-old child treated at Cooper, for whom many doctors might recommend surgery. His initial X-rays are shown below.

X-ray showing broken bone in five-year-old patient.

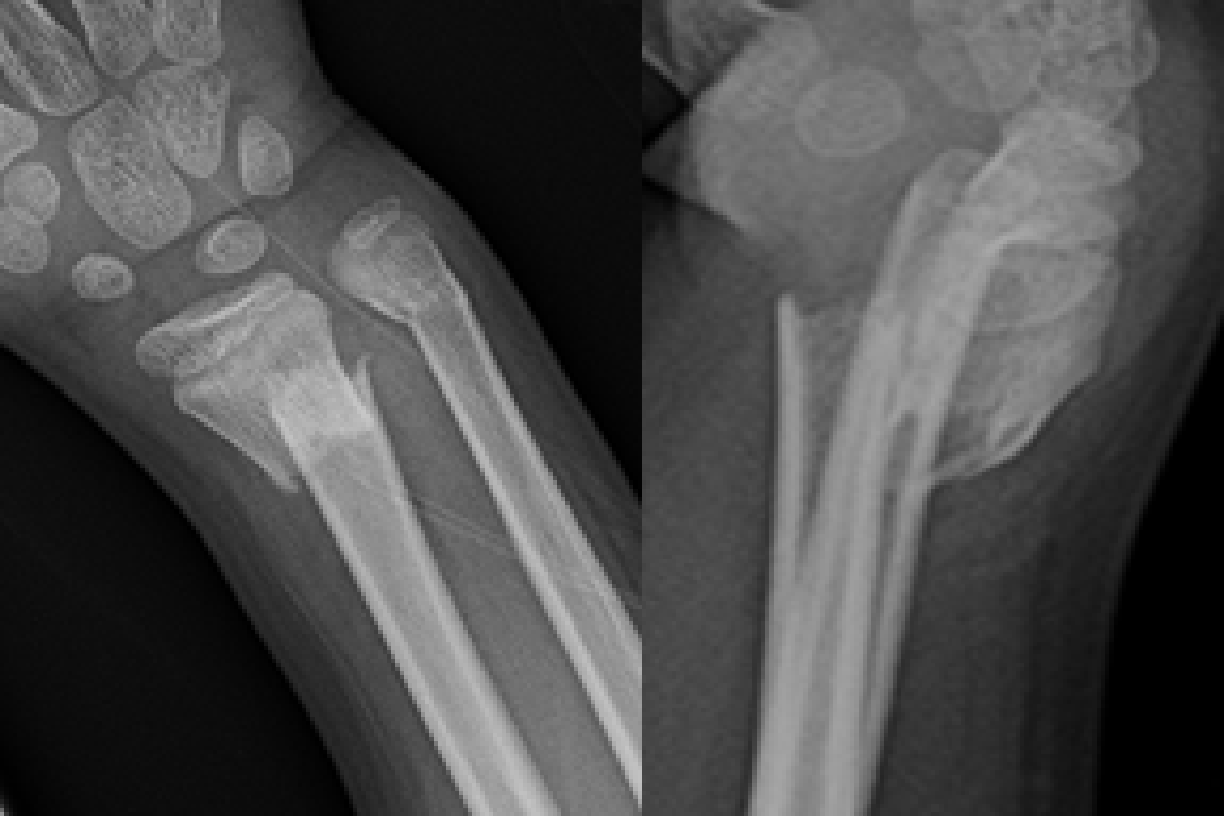

After discussion with the parents, the decision was made to place this child in a cast. Five months later, the results – shown below – are dramatic.

X-ray showing healed bone in five-year-old patient, five months after treatment without surgery.

The previous fracture can barely be seen. With time, the expectation is that it will be as if nothing ever happened. By remembering that kids remodel well, unnecessary surgery was avoided.

A recent study published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Izuka et al., 2012) supports this course of treatment. For a five-year period all patients treated at Children’s Orthopaedics of Hawaii for this type of wrist fracture were given a fiberglass cast and no surgery. All patients remodeled and had normal wrist function. Cast treatment was also calculated to cost only one-ninth as much as surgery.

Of course, not everything can be treated in a cast, and there are many times when surgery is necessary. Your doctor will be able to provide advice about the trade offs between casting and surgery. My personal preference is to embrace the remodeling potential of kids, and avoid surgery if possible. Hopefully you may never find yourself in this situation, but, if you do, know that there are often options other than surgery.

Rey N. Ramirez, MD

Pediatric Hand Surgeon

Cooper Bone and Joint Institute